Gustav Klimt & Adele Bloch-Bauer I: An Odyssey Through Nazi Germany … in English

Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I: An Odyssey Through Nazi Germany

Gustav Klimt’s Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I fame comes not only from its position as the epitome of his Gold Period but from it’s complicated history spanning almost the entirety of the twentieth century. In this article, Singulart discusses Klimt’s masterpiece and its history.

Who was Gustav Klimt?

Gustav Klimt (1862-1918) was an Austrian artist and the leader of the Vienna Secession movement, whose work would come to define the Art Nouveau movement. Born in 1862 in Baumgarten, Austria, Klimt was the son of a gold and silver engraver. Following his father’s artistic influence, he began studying at Vienna’s School of Applied Arts at the age of 14 where he took a range of subjects including fresco painting and mosaics.

During his studies he spent a lot of time copying the works of Old Masters in Vienna’s museums. He also sold portraits with his brother and worked for an ear specialist making technical drawings, all of which helped Klimt develop a mastery for depicting the human form.

After completing his studies he opened his own studio in 1883, specializing in mural paintings.

His early work was classical, in keeping with 19th century academic painting, as is exemplified by his murals for the Vienna Burgtheater (1888), for which he was awarded the Golden Order of Merit by the Emperor Franz Josef.

In the early 1900’s he took his interest in the human form, more specifically the female form, further in a series of erotic drawings of women. From here, Klimt shed the classical pretenses for depicting the human form with propriety and began to explore themes of human desire, dreams and mortality through richly symbolic compositions which would come to define his style.

Despite the enduring influence of the city’s traditional government and artistic establishment, Vienna at this time was a hub of bohemian artistic activity, and Klimt’s works fit in perfectly with the experiments other avant-garde cultural figures such as Otto Wagner, Gustav Mahler and Sigmund Freud.

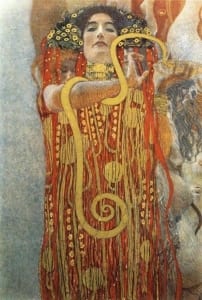

He continued his rebellious experimentation with his commissioned mural for the Kunsthistorisches Museum, where he represented the history of art from Egypt to the Renaissance through human female figures, rejecting any historical or allegorical pretext that would have deemed such portrayals acceptable by the establishment.

This mural also marked the beginning of Klimt’s “femme fatales”, depictions of expressive, seductive women.

In 1897, along with other members of Vienna’s Avant-Garde, Klimt founded and became the leader of a radical group called The Vienna Secession.

His work became increasingly concerned with psychology and sexuality and women appear as his repeated favourite subject matter. A trip to Ravenna in Italy, where he encountered Byzantine art, led to his famous Gold Period. Klimt died at the age of 55 and despite having mentored artists such as Egon Schiele and Oskar Kokoschka his legacy was somewhat overlooked until much later in the twentieth century.

The story behind Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I

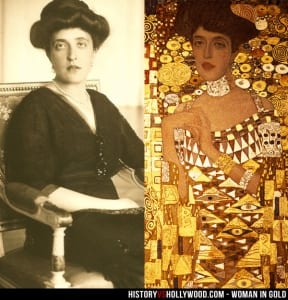

Adele Bloch-Bauer (1881-1925) came from a wealthy Viennese Jewish family, her father was the director of the largest bank in Austria-Hungary as well as the general director of Oriental Railroads. In 1899 her parents arranged her marriage to Ferdinand Bloch, a banker and sugar manufacturer. At the time she was 18 and he was 35 and they both changed their names to Bloch-Bauer and never had children. Adele was renowned for her salons, where she invited intellectuals and creatives into their home and it was in the late 1890’s that she met Gustav Klimt.

Gustav Klimt, Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I, 1903-1907

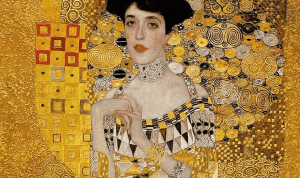

Ferdinand Bloch-Bauer commissioned Klimt to paint his wife’s portrait in 1903 with the intention of gifting it to her parents as an anniversary present. Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I became one of Klimt’s most elaborately prepared paintings. He made over a hundred sketches and in 1903 he studied the Byzantine gold mosaics in the Basilica of San Vitale in Ravenna which had a huge influence on his gold period and on the Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I, which is considered to be the epitome of this period.

Klimt developed an elaborate technique in the making of the Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I, with only her face and hands painted in oil, the rest of the 138 x 138 cm canvas is covered in gold and silver leaf onto which Klimt used Gesso to apply decorative motifs in bas-relief.

The final work, completed in 1907, depicts Adele Bloch-Bauer on a golden chair in front of a detailed, patterned gold background. She is dressed in a fitted gold dress, decorated in delicate geometric forms in blue, black and silver to contrast against the predominant gold. The dress merges into the background in places, so that Adele’s face and hands stand out in stark contrast against the flow of gold.

The overall effect of this portrait has been described as sensual and an embodiment of femininity. Within the details of the composition and the multitude of patterns and forms can be identified many symbols and influences ranging from the Byzantine to Greece. Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I has also been described as presenting Adele more in the style of a religious icon than a secular portrait.

From Austria to America

In addition to exemplifying Klimt’s Gold Period, Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I is also renowned for its tumultuous history. In her will, Adele stated her desire for Ferdinand to leave all the artworks by Klimt in their collection to the Austrian State Gallery in Vienna after his death. After the painting’s completion in 1907 it hung in the Bloch-Bauer’s home and after Adele’s death, Ferdinand hung the painting in Adele’s bedroom in homage to her. Over the next few years, the painting was lent for exhibition across Europe and in 1937 it was displayed at the Paris Exhibition.

In 1938, Ferdinand fled from Austria to his Czechoslovakian castle after the invasion of the Nazi’s and from here he fled to Paris before settling in Switzerland, having left the vast majority of his fortune behind in Austria. The Nazi Regime falsely accused him of tax evasion as an excuse to seize as much of his property as they desired. The Nazis divided and sold off much of the Bloch-Bauer art collection and the Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I ended up in the Galerie Belvedere. In 1945, the year of his death, Ferdinand rewrote his will in which he left his entire estate to his nieces and nephews, although he made no reference to the Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I, which he assumed was lost forever.

In 1946, despite the Annulment Act which voided Nazi transactions, and the efforts of the lawyer hired by the family, Dr. Gustav Vinesh, the Bloch-Bauer’s were forced to relinquish most of their art collection, including Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I, to the Austrain State, supposedly on the basis of Adele’s will.

In 1998, after the Austrian government introduced the Art Restitution Act which aimed to re-examine the art stolen by the Nazis, the investigative journalist, Hubertus Czernin, published a report claiming a ‘double crime’ had been committed with regards to the Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I: firstly the theft by the Nazi’s and secondly the Austrian Government’s refusal to return the painting to the family.

This led to Adele and Ferdinand’s niece and heir, Maria Altman filing a claim with the restitution committee to recover six paintings, including Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I, which was refused again on the grounds of Adele’s will.

Consequently, Altmann sued the Austrian Government and the Belvedere Gallery in the US Court and eventually won, with the Supreme Court ruling that the paintings had been stolen, in 2004. In 2006, Altmann sold the Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I to Ronald Lauder for $135 million, at the time the highest price paid for a painting, and it remains on display in his gallery, the Neue Gallery in New York …